Introduction

Vegetarian food in Japan has always felt confusing to me as an Indian traveller—exciting, but tricky. As a travel blogger, I love discovering food that connects culture, health, and local stories. On my Tokyo journey, I followed the recommendations of Tokyo-based Indian chef Tejas Sovani, whose deep respect for Japanese cooking and vegetables completely changed how I experienced food.

Table of Contents

ToggleFrom calm temple meals to quick street bites, this guide is my first-hand take on where to eat food, explained simply, clearly, and honestly.

Where Vegetarian Options Exist in Japan?

Exploring food with\insights helped me realise that plant-based eating here is not limited—it’s thoughtful. Japanese cooking treats vegetables with care, seasonality, and balance. Below are places where I enjoyed vegetarian food, each offering something unique.

Also Read: https://travellergossip.com/japans-top-food-city-best-eats-picked-by-a-local-chef/

Traditional Foundations of Vegetarian Food in Japan

The roots of vegetarianism reach far deeper than recent food trends or the global vegan movement. Long before the word “vegetarianism” went on to become international, Japanese food was already steeped in plant-based philosophy informed by geography, religion, and seasonal living.

The Japanese don’t even have a single word for dumplings. Rice has always been the staple food. It’s pretty much served with every meal, and functions as a blank slate that magically pairs with vegetables, tofu, and legumes. Rice, noodles, including soba (buckwheat) and udon, are the country’s everyday foods, frequently consumed unadorned with vegetables or light seasonings, both of which lend themselves to being adapted for vegetarian diets.

Rice, Noodles, and Plant-Based Staples

Vegetarian fare in Japan is rooted in simple, plant-based foods that have been staples of everyday life here for millennia. Long before the era of modern vegetarian status, Japanese menus were already naturally grain-based and plant-forward.

Rice as Base for Any Meal:

We eat steamed white rice and mixed-grain rice with almost every traditional meal. Rice provides sustenance, equilibrium, and satiety, so it is the obvious base for vegetarian food.

Soba (buckwheat noodles):

Soba is a staple and is frequently lighter and healthier than wheat noodles. It’s usually served cold, zaru soba, or with vegetable toppings and can easily be vegetarian (as long as you don’t include fish-based broth).

Udon (wheat noodles):

Thick, ribbony udon noodles are a pillar of comfort food. Though broth often has dashi, plain udon served with vegetables or dry-style preparations can go well for vegetarians.

Tofu in endless forms:

It can be grilled, silken, fried, chilled, or simmered. From agedashi-style to soft, silken blocks just dressed with soy sauce, tofu is still one of the main sources of protein for vegetarian dishes in Japan.

Center on seasonal vegetables:

Japanese cooking celebrates seasonality. Vegetables are often consumed raw or lightly grilled, steamed, pickled, or simmered, showcasing that natural goodness without denaturing it with heavy sauces and fat.

Combined, these staples create the backbone of everyday vegetarian eating in Japan, an availability that’s more successful than many people imagine for travelers.

Fermented Foods and Plant Proteins

Fermentation is a foundation of Japanese cooking that adds dimension, nutrition, and flavor longevity to plant-based fare. Not only are these readily available, cheap, and can be found across Japan, from supermarkets to ramen bars.

Miso (fermented soybeans):

Miso, which imparts deep umami and warmth, is also part of soups and marinades, along with sauces. Although miso soups in many restaurants are made with fish stock, miso is itself vegetarian and a staple of plant-based cooking.

Typical cost:

- ¥100 to ¥250 per bowl of miso soup (vegetarian at temples or vegan cafés)

- ¥300-¥600 for a small pack of miso you obtain at grocery stores

Natto (fermented soybeans):

A pungent but nutrient-dense staple, natto is full of protein, probiotics, and vitamins. It’s a staple in Japan, often eaten with rice for breakfast, and one of the country’s most affordable sources of protein.

Typical cost:

- ¥80–¥150 each (supermarket, convenience store)

- Tsukemono (pickled vegetables)

Cucumbers, radish, cabbage, and eggplant are pickled to provide crunch and acidity to dishes. A Tokyo essential, served almost everywhere as a side dish, tsukemono is naturally vegetarian and seasonal.

Typical cost:

- ¥100–¥300 as a side dish

- ¥200–¥400 for small packaged varieties

Edamame:

Young soybeans served lightly salted are a popular snack on restaurant and izakaya menus, featuring that clean plant protein in its most honest form with no added anything.

Typical cost:

- ¥300–¥500 at restaurants

- ¥150–¥300 per store-bought package of edamame

These fermented foods and soy-based proteins are responsible for making vegetarian food not just filling, but also budget-friendly. For travelers, they provide inexpensive nutrition, cultural validity, and a variety of vegetarian options to nourish you, aid in your digestion, and keep you feeling fit during the journey.

Hidden Ingredients That Can Confuse Vegetarians

When I first started eating food, I realised that some dishes looked completely veg but weren’t. The biggest surprise is fish stock (dashi), which is used in soups, noodles, sauces, and even vegetable dishes.

Nothing is done intentionally; it’s just part of traditional cooking. Once I learned to ask clearly and double-check ingredients, finding vegetarian food in Japan became much easier and stress-free.

The Dashi Problem

When I started eating food, I learned that things aren’t always what they seem. And even those dishes that look totally plant-based may be concealing animal ingredients. The typical thief is dashi, a lively stock from fish (traditionally bonito flakes). Dashi is all over the place, in soups and noodle broths, simmered vegetables, and even sauces.

Some other sneaky ingredients I had to look out for were:

- Vegetables or tofu showered with shavings of bonito flakes

- Sauces of anchovies for vegetables or side dishes

Chinese stocks are in the form of a very flavorful liquid that is used as a base for sauces and soups, and also to moisten rice and meat.

This struck me as surprising and even a little confusing for someone who eats food. You could order something that seems to be safe, miso soup, say, or the vegetable tempura, only to learn it’s spiked with fish stock. It’s not designed to fool anyone; it is simply how traditional Japanese cooking has evolved over centuries.

Why Asking for “Vegetarian” Isn’t Always Enough

I had learned the hard way that you can’t just say “I’m a vegetarian”. The word is a borrowed one, and local definitions of it are divided. Others consider it okay to eat fish, eggs, or small quantities of flesh. Which means that your “vegetarian” dish might not actually be all plant-based unless you specify.

I find that it helps to:

- Get specific with what you don’t eat: chicken, pork, beef, seafood, fish stock, and so on.

- You can also use a translation card, written in Japanese, that explains what your dietary restrictions are

- Read the ingredients on menus or labels, particularly when it comes to packaged foods or soups

- Ask staff and, if in doubt, ask again as there may be hidden animal products in even familiar dishes.

I had already taken firm control of what I could and couldn’t eat, which is restorable.” Make it a vegetarian. Went well beyond: precise dieting, but once I’d started being almost pedantic about my food choices, traveling as a vegetarian in Japan became much more manageable.

Shojin Ryori: Japan’s Traditional Vegetarian Cuisine

Shojin Ryori is a centuries-old Buddhist meal, made entirely from plant-based ingredients to nourish both body and mind.

Buddhist Roots of Vegetarian Food in Japan

When I initially discovered Shojin Ryori, traditional vegetarian cuisine, I understood it’s so much more than the food; it’s a way of living. Shojin Ryori originated with Zen Buddhism, which was introduced to Japan around A.D. 538.

The principles behind Shojin Ryori are truly profound:

- Ahimsa (non-violence): All ingredients are obtained from plants, indicating respect for all living things.

- In season: The meals feature what’s fresh and local, which makes them nature-connected.

- Zero waste cooking: There’s no wastage here; stems, leaves, and peels often turn into stocks or garnishes.

- Balance: Food is prepared with care and attention, focusing on balance, nutrients, and mindfulness.

What Shojin Ryori Meals Include

When I first experimented with Shojin Ryori at a temple in Kyoto, I was struck by how simple and flavorful the food is. A typical meal includes:

- Handmade tofu: Soft or firm, and sometimes grilled or simmered; It offers a high protein content.

- Mountain greens: Seasonal fresh greens, root vegetables, and wild herbs, which are boiled or pickled.

- Sesame base: Nutty condiments that accentuate flavors without drowning out what the vegetables actually taste like.

- Brothy vegetable things: Instead of fish or meat for their depth, flavors come from kombu (seaweed), mushrooms, or miso.

Shojin Ryori is generally vegan, although some of the modern temples may add a little dairy. Strict vegans, for instance, will always want to check in advance.

To omnivores, Shojin Ryori is not just about food; it’s an experience. The dishes are served in small, plated portions that are lovely to look at and encourage you to eat slowly, to savor the flavors, the painting-gold leaf environment, and connect with your cultural spirit.

Modern Vegetarian Food in Japan’s Cities

In cities like Tokyo, Kyoto, and Osaka, vegetarian food has evolved into a creative and diverse scene, blending traditional flavors with innovative plant-based dishes that make eating meat-free exciting and accessible.

Growing Vegan & Vegetarian Awareness

Over the last several years, I’ve also seen a great deal of momentum around vegetarian food in Japan, particularly in major hubs like Tokyo, Kyoto, Osaka, and Yokohama. Restaurants, coffeehouses, and even convenience stores are finally beginning to cater to vegans and vegetarians, making life easier for omnivore travelers like me who might otherwise stress over meal time.

One useful tip I’ve picked up is to seek out official vegetarian or vegan certifications, which let me know if a restaurant can be trusted for a vegetarian diner. Here are some of the most trusted accreditations:

- Vegan Society

- Vege Project

- Vegetarian Association

Spotting these symbols on menus, or even just on storefronts, is instantly reassuring that your food will be 100 percent plant-based (or at least that the people working there will get what you’re about when it comes to dietary needs).

Innovative Plant-Based Japanese Cuisine

Most exciting to me about vegetarian food in these cities is the ingenuity of contemporary chefs. They’re rethinking age-old recipes while making sure they are purely plant-based. Some highlights include:

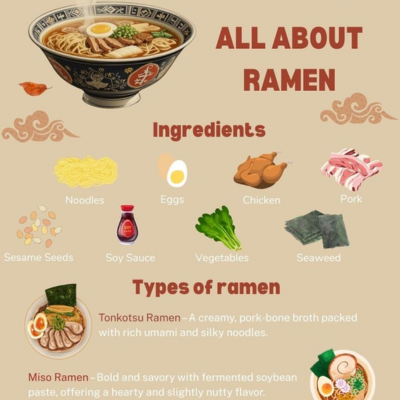

Vegan ramen: Filling, flavorful broths of vegetables (or mushrooms or seaweed) plus noodles and garnishes, such as tofu, bamboo shoots, and greens.

Tofu cheese: Japanese cooks are using tofu to make cheese with creamy, cheese-like textures for use in salads or pasta.

Meat substitutes: Whether vegan chicken or burger patties, these foods provide vegetarians with tastes they recognize while avoiding animal products.

Plant-based eggs: Novel soy or chickpea varieties that mimic scrambled or omelet, hot in cafes and brunch joints.

And even people who usually partake of meat sometimes give these restaurants a whirl just because the food is so tasty and inventive. For me, the experience of eating at modern vegetarian spots is like a culinary adventure, tradition meets innovation with each bite.

Finding Vegetarian Restaurants in Japan

Finding vegetarian restaurants has become much easier in recent years, especially in big cities, thanks to specialized apps, certification labels, and online guides that help travelers discover safe and delicious plant-based options.

Useful Vegetarian Restaurant Platforms

When I first visited Japan as a vegetarian,it felt like virtually nobody “got” vegetarian food in restaurants. Eventually, I found several online services and apps that help me find safe, tasty vegetarian options no matter where I am in the country.

Here are some of the most useful sites:

Happy Cow: This is my destination app for restaurants that serve Vegetarian and Vegan meals across the world. In Japan, it compiles hundreds of options in big cities like Tokyo, Kyoto, and Osaka, along with reviews, photos, menus, and directions. It’s helpful if you are out exploring and don’t know an area well.

Vegewel: Japanese website and app covering vegetarian-friendly and vegan restaurants. It gives you a lot of specific information about menu items, price point, and whether or not the restaurant adheres to strict vegan or vegetarian standards.

Japan VegeMap: A great resource for residents and tourists alike, VegeMap showcases vegetarian-friendly cafés, restaurants, and specialty stores. It’s a convenient way to plan your meals ahead of time or look up recipes on the fly.

Japan Vegetarian Society Restaurant Guides: The Japanese Vegetarian Society’s official guides on their certified restaurants. The listings frequently utilize certification logos, which help to make the restaurant’s offerings more trustworthy.

For any vegetarian traveler, these are indispensable.They save time, eliminate stress, and help make it so every meal is both safe and enjoyable.

Final Thought

The journey through food taught me that plant-based eating here was contemplative, seasonal, and purposeful. With the guidance of Chef Tejas Sovani and my own trips, I discovered that Tokyo is not impossible for vegetarians – you need to know where to go.

If you’re an Indian traveler or a vegetarian, do me a favor: Don’t be afraid. Food is delicious, surprising, and most definitely worth your time.

Also Read: https://travellergossip.com/top-10-amazing-taco-spots-in-the-u-s-stun/

FAQ: Vegetarian Food in Japan

1-Is vegetarian food in Japan easy to find?

Vegetarian food in Japan is accessible in cities but requires planning in rural areas.

2-Is Japan vegan-friendly?

Japan is improving, especially in urban centers, but hidden ingredients remain a challenge.

3-Can vegetarians survive on convenience store food?

Yes, with careful label reading and limited sauce use.

4-Is Buddhist food always vegan?

Traditionally yes, but modern variations may include dairy.

About the Author

Khushi Vaid is a travel blogger and lifestyle writer who focuses on mindful travel, food cultures, and real-world travel experiences. Through Traveller Gossip, she shares honest insights that help readers travel smarter, eat better, and connect more deeply with the places they visit.